Like anyone else in the slum, no one ever gets to know enough about the other.

No one asks where the others came from or what they did before. Since everyone comes hoping to make it in the big city, only to end up stuck in the slum, rarely do we discuss our previous lives.

With the dreams that inspired these journeys — or the journeys our parents — now differed, we allowed the past to sleep. But often, a ninja would surprise the slum with something from their previous lives: like one time, a toilet cleaner/entrance fees collector turned up in a Winner Classic suit, dripping like a member of the Legislative Council.

We started calling the man, LEGCO. But I learned that the fellow was the manager of the then recently defunct Uganda hotel in Mbale. He had ended up with us.

There was another time when white tourists were taking pictures of the slum, and a charcoal seller eavesdropped their conversation and started explaining things to them in perfect Russian. What broken dream lived in the chest of this Russian-speaking slumdweller!

In that spirit, no one knew much about Mama Night’s background. She seemed to have emerged from nowhere and all of the sudden established one of the most attractive alehouses in Mafubira. She seemed like a woman who had big dreams, but not impatient to achieve them.

She seemed uneducated but somehow well-cultivated and had quickly acclimatized to the hustles of the slums. No one ever asked whether she had a child called Night; we simply called her Mama Night. She ran her business — rather businesses — well; spoke fairly good English, but didn’t signal to much learning.

Remember this is the 1990s, and unlike today, being fluent in English didn’t mean much because everyone spoke it well. Mama Night was not known for witchcraft, which was widespread in the slum. Bar owners, hawkers, girls of the night, and vendors of all kinds of things were renowned for doing voodoo.

It must have been her good liquor (so they said), and possibly her leg business that softened the male gender when dealing with her. She seemed special. If it was calling out people in the morning for community service, such as cleaning sewers, no one knocked on her door.

Not that she was a bad person, but no one made her do anything out of community ritual. Tax collectors in the slum never touched her liquor business. Her other day business—selling leg—was known to only her clients, who, as you could have guessed, included the tax collectors. Like most of us connected to electricity or water, she had both her connections irregularly done. But she never paid any bribes. Uganda Electricity Board workers simply liked doing things for her.

MAMA NIGHT “FALL IN THINGS”

I was returning from school one day when I found a group of slum-women talking loudly, angrily and asking “how could she,” without finishing their sentences. Who and what had she become, I wondered. Then one of them said, “how could a renowned whore become our Defence!

Still, I didn’t understand. Then, slowly, I made out the different lines of the conversation: Mama Night had become a member of the Resistance Council seven-people committee. She had become the person in charge of Defence.

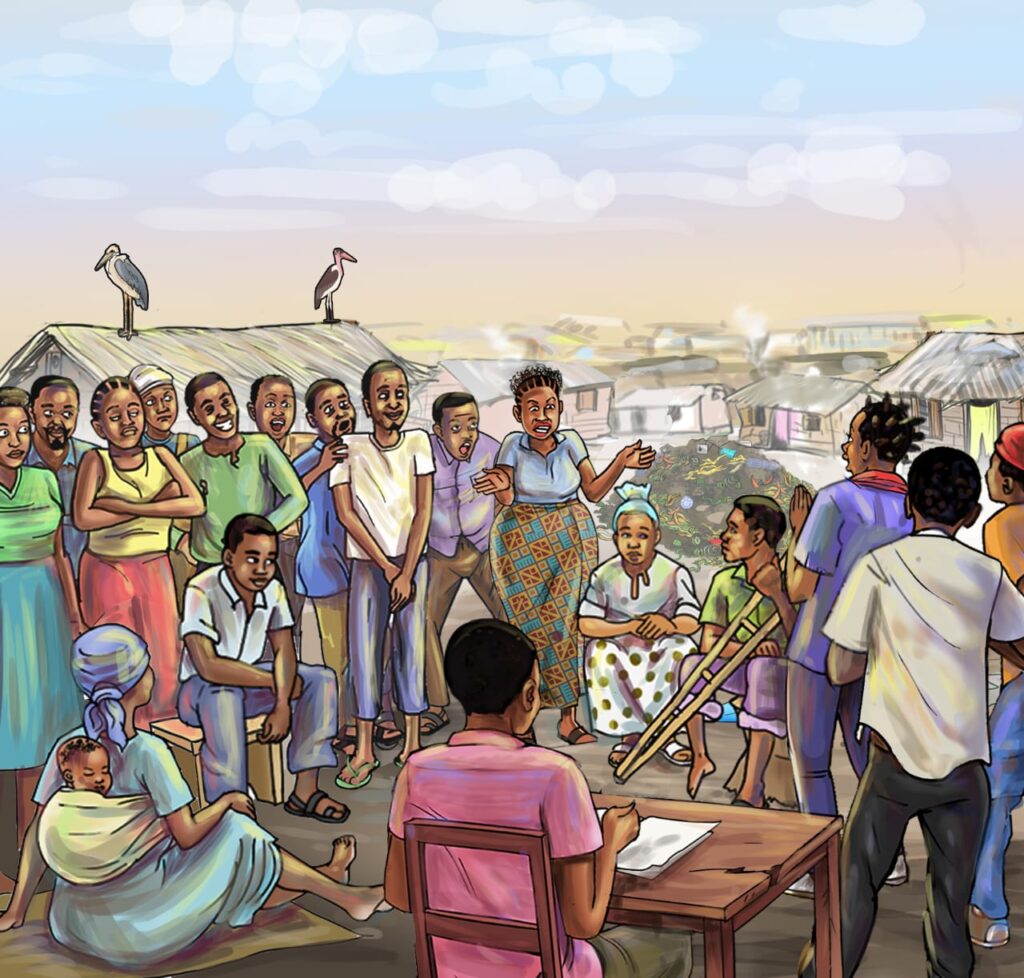

After having my welcome-back-from- school meal, I caught up with the rest of the boys, and the story became clearer. Mama Night had only showed up for the elections meeting as one of the residents.

A voter at most. There were no elaborate elections then as today. Local leaders were often elected at meetings either under a tree or in a makeshift hall. The tellers of the story stressed that Mama Night had no interest in politics, and had only jokingly, rhetorically, signalled to some interest.

“But one day, you people, I will become your Defence,” she had started. “It seems all these men cannot even defend us against this garbage,” she had spoken softly, almost inaudibly.

“Because look at the rubbish in front of Mama Paulo’s house!” Mama Night had actually attended so as to complain about the garbage in front of her friend and neighbour’s house.

“Yes, I think Mama Night would be our answer for Defence. Our only answer,” an elder responded.

Once Tata Tendo, one of the most respected elders of the slum, endorsed Mama Night, all the other men aspiring for the position fell silent. She was unopposed. “Defence” quickly became her other name – or actually her only name.

But the position didn’t mean much then, except being in the position to take some bribes from people caught from small misdemeanours here and there. Well, as friends of hers — the small boys always playing in her house, eating her food, and dancing in her bar — we gladly welcomed the news and prepared to go congratulate her. If Madam Defence had fallen in things, we were in those things together. And we would heckle, if need be, stone, whoever badmouthed her.

MAMA NIGHT EVOLVES

But in a matter of months, Mama Night had revolutionised a hitherto almost meaningless position into something bigger than the RC1 Chairman himself. It was her appetite for bribes and the calmness with which she went about it. She demanded for bribes from all sorts of businesses and all sorts of dealings — as long as some wrongdoing could be deciphered.

Remember, this is a slum and almost everyone has something illegal going on She got involved in anything and everything in the slum: tax collection, garbage collection, water and electricity connection, latrine fees, newcomers, drug dealers, food vendors, name it. She often said, Mafubira Zone B has to be secured.

She was Defence. And then she would ask in crisp Lusoga, “Buti omusirikale wayimwe talye?” Consider this for example. Those days, it was mandatory to have all children of school-going to be in school. If you were unable to pay school fees for your children, you had to be able to pay Mama Night to let your kids loiter in the slum.

Mama Night still kept her bar, and also never lost her side hustle, leg-selling. But being Defence became more profitable than anything she had ever dreamed of. Her bar started expanding and colonising neighbouring houses. It was her neighbour and former friend, Mama Paulo to lose her house. It became an extension of her bar. More power, more money, more clients.

Again, us the boys of the neighbourhood, we cheered her on. There was more coming. It seems after a peculiar threshold, Mama Night lost her head and decided to go rogue. She became a slum pirate — something like an open thief. If your business was doing well, you had to make sure, in addition to paying your taxes, you were also friendly to Mama Night.

To begin with, you had to drink from her bar. But then again, you had to give her a special envelope. If you were unfriendly, uncooperative, you immediately became the next victim of robberies. Your skull could be broken.

All of a sudden, robberies and violent break-ins became part of the slum. Sometimes, your small business would be set on fire if Mama Night deemed you unfriendly. Remember, Taata Tendo, who received complaints about Mama Night, drank at Mama Night’s bar.

But then one day, at the end of one small village meeting, Mama Night was not Defence anymore.

yusufkajura@gmail.com

The author is a political theorist based at Makerere University.

Source: The Observer

Share this content: